Istanbul, Turkey

Istanbul is famous as one of the world’s truly great cities; with its exotic Eurasian mix; filled with architecture (palaces, mosques, the grand bazaar), with extensive arrays of artifacts and objects d’ art attesting to a vibrant and rich history as a former capitol (and empire in its own right), center of international trade, learning and education.

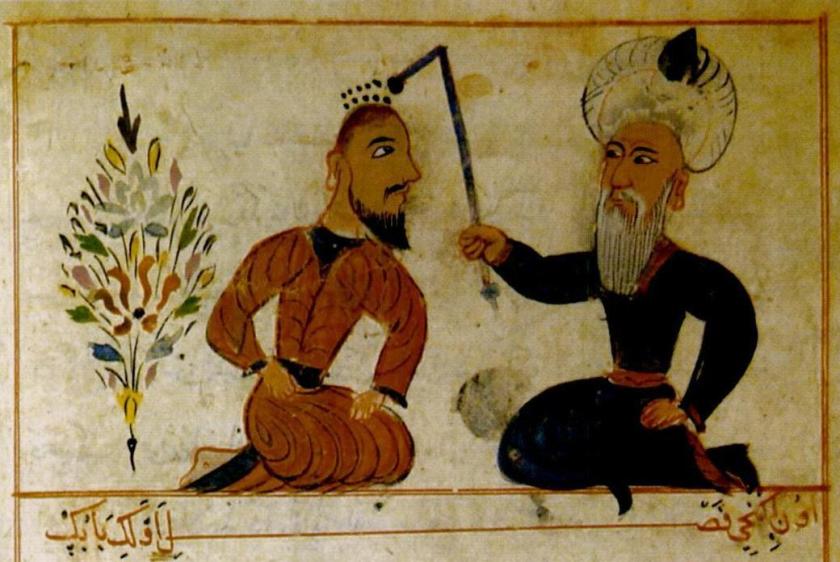

From the earliest years of the city (Constantinople), it has been a center of technology, cultural and societal advancement. While many people know about and visit (the cisterns) of the Valens aqueducts, a fourth century AD water delivery system which provided the city with fresh water, few people know that Istanbul along with places like Iran (Persia) provided us with the foundations of medicine.

Since ancient times, learned scholars and physicians in this part of the world advanced our understanding of human anatomy, physiology, disease and medicine. Much of this knowledge was lost/ banned in other parts of the western world due to ignorance or religious-based beliefs which resulted in countless suffering in Europe and the Americas.

*(If you aren’t much of a historical scholar, just watch any of several excellently researched movies, and even some more ‘so-so’ series such as London Hospital or the new American series, “The Knick” to see how medicine fared without the basic knowledge gained by Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu and other middle eastern physicians over the centuries.)

Tombs for Sultan II Mahmud, Sultan II Abdulhamid, Sultan Abdoulaziz and valued members of their courts.. now look closer.

With such strong ties to the history (and advancement) of medicine and nursing in Istanbul, it is no surprise that my work has brought me to the doorstep of modern civilization, to Dr. Mustafa Yüksel, pectus repair and 3-D printing.

Dr. Mustafa Yüksel

Dr. Yüksel is a cardiothoracic surgeon and the Chief of Thoracic Surgery and faculty professor for the school of Medicine. He is the former president (for three consecutive years) of the Chest Wall International Group and spearheads Pektus (the pectus project) which is a program aimed at training surgeons, educating people and performing pectus repair.

He attended medical school at Ankara University and completed both his surgical residency and thoracic surgery fellowship in Ankara at the Ankara Ataturk Education and Research Hospital. He briefly worked as a thoracic surgeon at the Camlica Military Hospital before becoming the Chief of Thoracic Surgery at Heybeliada Education and Research Hospital.

Dr. Yüksel spent a year as a visiting fellow at the Royal Brompton Hospital with Dr. Peter Goldstraw in London, England before returning to join the faculty at Marmara University Hospital. In 2004, he studied with Dr. Donald Nuss, of Norfolk, Virginia. Dr. Nuss is the inventor of the minimally invasive pectus repair, the “Nuss procedure“.

In 2005, Dr. Yuksel performed his first Nuss procedure for repair of a pectus defect. Since then, he has performed this procedure over 600 times. He estimates that in the last several years, he has performed 150 pectus repair procedures annually. Dr. Yüksel and Marmara University have become the major center for chest wall surgery in Turkey. The program also attracts surgeons internationally, to learn more about the center. In the last month alone, Dr. Yüksel hosted surgeons from the United Kingdom, the Ukraine, Poland, Holland and other parts of Europe. The majority of these surgeons have come to see Dr. Yüksel’s titanium carinatum bars.

Dr. Yüksel has also written several textbooks and chapters on thoracic surgery.

Prof. Mustafa Yüksel, MD

General thoracic and cardiovascular surgery

Ministery of Health of the Republic of Turkey

Marmara University Pendik Training and Research Hospital

Thoracic Surgery Department

7th Floor, F wing

Fevzi Cakmak Mah, Mimar – Sinan Cad. No 41

34899 Ust Kaynarca/ Pendik

Istanbul, Turkey

(+90) 216-625-4545 ext. 3580

Marmara University Hospital

Marmara University is the second largest university in Turkey and was founded in 1883. The university serves over 60,000 students. The main campus is located in the central Istanbul neighborhood of Fatih but the School of Medicine and University Hospital are located across the Bosphorus river in Kadikoy. (A newer, larger 600 bed facility is being built in nearby Maltepe but is still under construction).

As a public hospital, Marmara University sees patients from all over Turkey and from every social class.

The university hospital has a large thoracic surgery program, with five thoracic surgeons on staff, which allows the thoracic surgeons to sub-specialize. Dr. Yüksel sub-specializes in chest wall repair and tracheal surgery.

During my visit, I also met with Dr. Dr. Bedrettin Yıldızeli, a thoracic surgeon who is currently involved in developing a pulmonary arthrectomy program for patients with chronic pulmonary emboli. (These patients will develop pulmonary hypertension and right-heart failure if untreated.) The current prognosis for this growing patient population is quite grim, so an advancements in this area will certainly be welcomed. Dr. Yildizeli is also interested in thoracic surgery applications using the Davinci robot.

Pectus excavatum versus Pectus carinatum

The easiest way to remember and differentiate between these two conditions is to remember: In or out? Pectus excavatum or “funnel chest” is a chest wall defect that causes an inward deviation of the sternum. Think ‘excavate’ as removing from the ground or bringing something upwards/ outwards.

Thus, pectus carinatum or “pigeon breast” is an outward bowing of the sternum. I don’t have any cute little sayings to remember this one.

In extreme cases, these defects can compromise the function of the heart, lungs and mediastinal organs.

The Nuss Procedure

Historically, pectus repair was performed using open surgery, but in 1987, Dr. Nuss invented a procedure using steel bars inserted via small (2 to 3 cm) incisions into the chest. The bars are placed into position and affixed with sternal wires. The bars force the sternum and chest wall to the appropriate shape.

When used for pectus excavatum, the bars force the sternum outward from inside the chest. When used to correct pectus carinatum, the bars are placed more superficially – beneath skin and muscle but outside (and over, not under) the sternum. These bars are usually visible as a thin line in most patients. (Most patients with this condition are very thin.)

These bars usually remain in place for around two years. (They may be removed earlier if complications develop).

However, there are several problems related to this condition and the Nuss procedure. Much of Dr. Yüksel’s work has been aimed at corrected problems related to the hardware used for this procedure.

Metal Allergies

The usual Nuss bars are made of stainless steel and require sternal wires or similar fixation to remain in place. The stainless steel material can be problematic due to the incidence of nickel and steel allergies in some patients. While Dr. Yüksel performs pre-operative allergy testing in all patients prior to surgery, and takes a complete history to determine a pre-existing allergy, up to three (3%) of patients without pre-operative metal allergies will develop one from continuous contact with the stainless steel bars. While these patients are given steroids and other medications to treat this allergy, it often persists, requiring bar removal.

Dr. Yüksel developed titanium bars to combat the problem of metal allergies. (The majority of patients are allergic to alloys or components in the stainless steel, particularly if nickel is used). These patients readily tolerate titanium.

One of the other technical problems encountered during this procedure is the inability to affix the bars to the chest wall securely. This happens more commonly in older patients who have less flexible bones. (As patients mature, bones become more rigid). The majority of patients undergoing this procedure are children, adolescents and teens but older patients often present after becoming symptomatic due to organ compression.

Using titanium bars can actually compound this problem, since titanium is a much stronger, less flexible material than stainless steel. So, Dr. Yüksel created a new way of securing the bars into position using either clips or screws – similar to the techniques used by orthopedic surgeons to stabilize a fracture.

The Yüksel Bars

Dr. Yüksel currently has three designs, two patented, with the third patent pending. He developed the first design in 2008, and several hospitals (6 or 7) are using his design for their repairs. These designs are also being used by other surgeons across Europe.

The different designs are used for different problems and allow the bars to be more readily customized for each patient. The bars are designed to be able to be used on very small children, pectus carinatum as well as older adults. (The average age of his patients is 17. The youngest patient was 6 years old – and he recently operated on a brother and sister in their late fifties. (The is a 20% familial risk.)

Each bar has adjustable plates for clip placement.

3-D Printing?

But Dr. Yüksel isn’t content to rest on his laurels. He is always thinking, creating and innovating. His newest project involves 3-D printing.

Dr. Yüksel is currently experimenting in creating customized implants for patients using a 3 D printer. The printing itself takes one to three hours, but the entire process takes considerably longer as patients undergo CT Scan reconstructions to allow Dr. Yüksel and his team to recreate a sternum, a thoracic vertebra or a tracheal implant.

His work is currently hampered by his materials – the plastic used for 3-D printing is too toxic for long-term human use, but he reports that new, safer materials are being developed in the United States. These non-toxic materials will allow surgeons to repair and replace damaged organs in a way that is not currently possible.

One final thought

During my visit, we talked about some of the specific thoracic conditions endemic to particular geographic areas. I mention hydatid cysts as an example from a previous interview. Dr. Yüksel laughs and reaches for a gallon-sized jar on a high shelf.

While Istanbul is a European city (with low rates of empyema and similar type infections), Dr. Yüksel talks about his thoracic surgery training in Ankara and many of the patients from rural areas. “I think, during my training, I removed about a thousand of these.” We talked about the epidemiology – and how it is often easily spread from seemingly innocuous sources, like cute little stray puppies.

So readers, when you see that cute stray dog during one of your travels? Don’t pet it. Or you might end up with one of these growing in your lung.

Selected bibliography for Dr. Yüksel

Bostanci K, Evman S, Yüksel M. (2012). Simultaneous minimally invasive surgery for pectus excavatum and recurrent pneumothorax. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012 Oct;15(4):781-2. Epub 2012 Jul 6.

Yüksel M1, Özalper MH, Bostanci K, Ermerak NO, Cimşit Ç, Tasali N, Yildizeli B, Fevzi Batirel H. (2013). Do Nuss bars compromise the blood flow of the internal mammary arteries? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013 Sep;17(3):571-5. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt255. Epub 2013 Jun 19.

Yüksel M, Bostanci K, Evman S. (2011). Minimally invasive repair after inefficient open surgery for pectus excavatum. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011 Sep;40(3):625-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.12.048. Epub 2011 Feb 20.

Yüksel M, Bostanci K, Evman S. (2011). Minimally invasive repair of pectus carinatum using a newly designed bar and stabilizer: a single-institution experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011 Aug;40(2):339-42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.11.047. Epub 2011 Jan 11.

Bostanci K, Ozalper MH, Eldem B, Ozyurtkan MO, Issaka A, Ermerak NO, Yüksel M. (2013). Quality of life of patients who have undergone the minimally invasive repair of pectus carinatum. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013 Jan;43(1):122-6. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs146. Epub 2012 Apr 6.

Umuroglu T, Bostancı K, Thomas DT, Yüksel M, Gogus FY. (2013). Perioperative anesthetic and surgical complications of the Nuss procedure. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2013 Jun;27(3):436-40. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2012.10.016. Epub 2013 Mar 30.

Ozyurtkan MO, Yildizeli B, Kuşçu K, Bekiroğlu N, Bostanci K, Batirel HF, Yüksel M. (2010). Postoperative psychiatric disorders in general thoracic surgery: incidence, risk factors and outcomes. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010 May;37(5):1152-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.11.047. Epub 2010 Feb 8.

Yüksel M, Bostanci K, Eldem B. (2011). Stabilizing the sternum using an absorbable copolymer plate after open surgery for pectus deformities: New techniques to stabilize the anterior chest wall after open surgery for pectus excavatum. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg. 2011 Jan 1;2011(623):mmcts.2010.004879. doi: 10.1510/mmcts.2010.004879.

Additional readings

About Pectus Repair

Medscape article with color photographs – article by Andre Hebra, may require subscription.

Jo WM, Choi YH, Sohn YS, Kim HJ, Hwang JJ, Cho SJ. (2003). Surgical treatment for pectus excavatum. J Korean Med Sci. 2003 Jun;18(3):360-4. pdf version: Nuss

Johnson WR, Fedor D, Singhal S. (2004). Systematic review of surgical treatment techniques for adult and pediatric patients with pectus excavatum. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014 Feb 7;9(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-9-25. While this article is dated (back to the early days of minimally invasive pectus excavatum repair aka Nuss procedure) it gives some good general information. The biggest limitations are in the comparisons of Nuss and the Ravitch procedure.

History of Thoracic Surgery and medicine in Turkey

I have provided a very limited list of citations (free full text only).

Batirel HF1, Yüksel M. (1997). Thoracic surgery techniques of Serefeddin Sabuncuoğlu in the fifteenth century. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997 Feb;63(2):575-7. pdf provided by Dr. Yüksel

Kaya SO, Karatepe M, Tok T, Onem G, Dursunoglu N, Goksin I (2009). Were pneumothorax and its management known in 15th-century anatolia? Tex Heart Inst J. 2009;36(2):152-3. Did Turkish physicians recognize and treat this condition a full 350 years before its first mention in western writings?

Heybeli N. (2009). Sultan Bayezid II Külliyesi: one of the earliest medical schools–founded in 1488. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009 Sep;467(9):2457-63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0645-1. Epub 2008 Dec 9.

Zuhal Ozaydim (2004). Some landmarks in the history of medicine in Istanbul. JISHIM. Several of these landmarks including some of the medical museums are open to the public. The Medical History Museum of Istanbul is located on Koca Mustafa Pasa in the Fatih neighborhood of Istanbul (Asia side) and is open o weekdays 8 am to 5pm, free.

*Undoubtably, some readers will take issue with these statements, but the abandonment of the teachings of many of the Moor physicians (brought to European courts), as well as the prohibition against human dissections and other religious prohibitions (from various Crusades, Inquisitions and other religious actions/ proclamations) retarded the development of modern medicine by several centuries. In reading historical medical literature, it is evident and (not infrequent) to see that important discoveries, diagnoses and treatments were made, possibly published and used in a limited circle and then forgotten, only to be “re-discovered” decades (or centuries) later.

Thank you to Dr. Cristian Anuz, cardiothoracic surgeon, of Santa Cruz de la Sierra for providing me with an introduction to Dr. Yüksel.